In the early morning hours of Monday, March 9, 1925, Mrs. Beatrice Fay Perkins returned to her Manhattan apartment at 168 W. 58th St., in the company of her escort, Milton Abbott, a cotton broker and family friend. The two had been to Reuben’s, 622 Madison Ave., where late night revellers often concluded the night’s gayety with coffee and cold beef sandwiches. There Mrs. Perkins became ill and asked Abbott to escort her home. The pair arrived at the apartment around 3 a.m.

A short time later, a group of masked bandits, using a crowbar and other tools, “chopped and hacked their way into the luxurious studio apartment.” Taking the pair by surprise, the gang of thugs first bound and gagged Mr. Abbott before setting upon Mrs. Perkins. As Mrs. Perkins screamed, one of the robbers punched her in the mouth and grabbed her by the throat. Another bandit grabbed her arm and twisted it as he tore a diamond bracelet and a diamond-studded watch from her wrist. He grabbed one of her rings and tore the flesh as he ripped it from her finger. Then her necklace was taken, and when one of her rings proved too stubborn to remove by conventional means, one of the bandits nearly bit her finger off trying to remove the ring with his teeth. Not satisfied with the jewels they’d ripped from her body, they cursed and punched Mrs. Perkins as they demanded more loot.

“Where’s the rest of your jewelry, quick, or we’ll kill you,” one of the bandits threatened.

“For God’s sake, don’t do any more,” Mrs. Perkins moaned. “It’s on the dressing table. There, in that casket.”

As she lay in a broken heap on the floor, one of the men gave her a final kick while another grabbed the jewels from the dressing table. Before they fled, the trio of bandits brutally beat Mrs. Perkins unconscious and choked her with a pillow to prevent her from crying out while they fled the scene. Then, without so much as disturbing a hair on Mr. Abbott’s head, they warned him not to move for ten minutes after they left, or they would kill him.

Once the attackers had left the apartment, it only took Abbott a few moments to slip his bonds. Once free, Abbott showed little compassion and rendered little aid as he merely clipped Mrs. Perkins’ wrist restraints with a pair of scissors. Then Abbott did a very curious thing. As Mrs. Perkins lay semi-conscious on the floor, bleeding from the severe beating she had just endured, Abbott did not call for an ambulance. He did not run to the neighbors for help. Nor did he call the police or summon a doctor. No, Milton Abbott, cotton broker, neglected to undertake any action the emergency situation required and, instead, ran straight to the office of Arnold Rothstein.

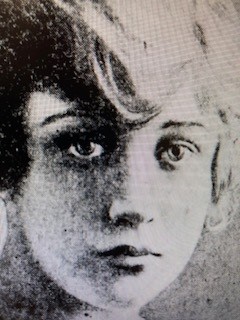

Estranged from her husband, Benjamin F. Perkins, wealthy proprietor of the Colannade Club, Beatrice Fay Perkins was described as a beautiful young woman and a frequenter of popular cabarets. “Young, slim and beautiful, clothed in the finest Parisian creations,” Perkins earned the nickname ‘The Sleeping Beauty,’ because she wore her jewelry in bed during a hospital stay only a few weeks earlier.

Badly beaten and abandoned by her companion, Mrs. Perkins left “a trail of blood behind her on the carpet” when she “dragged herself to the telephone” and called for help. Meanwhile, Abbott ran the few blocks to the office of Arnold Rothstein, 45-47 W. 57th Street where he was unable to locate Rothstein at that late hour. The following day, Mrs. Perkins told detectives, “Arnold Rothstein was the man who insured my jewels for me. That’s why we wanted to see if he could think of any way to trace them.”

Three o’clock in the morning seems like a rather strange hour to be contacting your insurance man about stolen jewelry. But Arnold Rothstein wasn’t just an insurance broker. He was a leading figure in the Manhattan criminal underworld with interests in gambling, bootlegging, narcotics and stolen jewelry. And Beatrice Fay Perkins wasn’t the first Broadway Butterfly to be severely beaten and robbed in her home. At least two women had already lost their lives to a gang of “Butterfly Guerillas.” However, this robbery, more than any of the others, appears to indicate that these attacks weren’t just random, unconnected events by unrelated gangs of thugs. But rather, one individual may have been the leading figure behind all of these brutal crimes.

Sources:

Brooklyn Daily Times

Brooklyn Eagle

Brooklyn Citizen